|

With the opening of Japan in 1854, after two hundred years of isolation, Japanese art and culture were introduced to the West, initiating a fascination that began in France and spread throughout Europe and America, continuing into the twentieth century. Japan's participation in world's fairs during this time, and the circulation of Japanese prints and decorative arts, further increased Western interest in Japan.

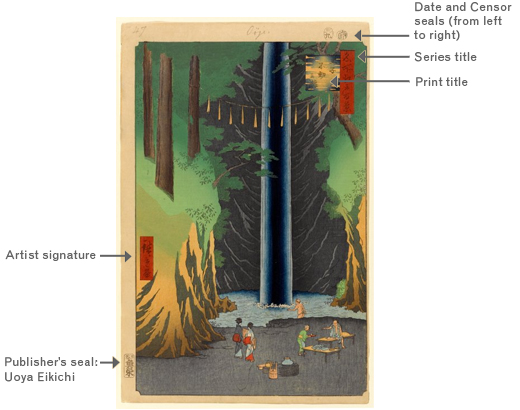

Ukiyo-e prints were particularly popular with Impressionist and Post-Impressionist painters and were studied by artists such as Claude Monet, Camille Pissarro, Edgar Degas, Mary Cassatt, Paul Gauguin, and James McNeill Whistler. Monet, for example, avidly collected the prints and displayed them in his home. Vincent Van Gogh, who with his brother Theo owned over four hundred examples, also organized exhibitions of Japanese prints. As the West entered a new century, Japanese woodblock prints provided an artistic alternative—in the use of color, perspective, and spatial structure—for presenting changes in society. Hiroshige and his One Hundred Famous Views of Edo occupy a special place in the Western reception of ukiyo-e. To many artists, prints from this series became important models for their paintings and prints. Individual images were either meticulously copied, as with Van Gogh's oil paintings based on Plum Estate, Kameido and Sudden Shower over Shin-Ohashi Bridge and Atake, or were more general sources of inspiration, evident in the adaptation of a particular landscape element or effect. The One Hundred Famous Views of Edo—in its evocation of urban life and the landscape of the city of Edo—complemented the vision of many Western artists of the time who were also concerned with the modern urban experience and its surroundings. After viewing another group of Hiroshige's prints at an exhibition in Paris in 1853, Pissarro wrote in a letter "the Japanese artist Hiroshige is a marvelous Impressionist." James McNeill Whistler was inspired by the Hiroshige prints that he once owned. One need only compare Whistler's etching Old Battersea Bridge, 1879, with Hiroshige'sKyobashi Bridge, 1857, to see how direct that influence was.

0 Comments

Edo was the city where the artist Utagawa Hiroshige (1797–1858) was born, lived, and died, and it is the place depicted in the majority of his landscape prints. Edo (renamed Tokyo in 1868) was the largest city in the world by the eighteenth century, with a population of more than one million people. Established first as a castle town in 1590, Edo became the de facto political capital of Japan in 1603. For the next two and a half centuries the country would be ruled by a lineage of feudal overlords (shoguns) and regional military lords (daimyo). Required to live in Edo on alternate years, the daimyo, with their families, household servants, and samurai, or military retainers, accounted for about half of the city's population. The remaining citizenry were mostly the many merchants and artisans (known as chōnin, or townspeople) who provided for the material needs of the city, as well as a substantial contingent of Buddhist and Shinto priests.

In this prospering commercial center, economic power resided with the wealthy townspeople. Artistic patronage and production no longer belonged only to the ruling elite but reflected diverse tastes and values. A new urban culture developed, valuing the cultivation of leisure that was celebrated in annual festivals, famous local sites, the theater, and pleasure quarters. The rich urban experience and the landscape of the time were documented byukiyo-e, or "pictures of the floating world," including woodblock prints like Hiroshige's One Hundred Famous Views of Edo. Since they could be purchased inexpensively—one print cost the same as a bowl of noodles—refined images became accessible to a wide audience. Hiroshige was born a low-ranking member of the samurai class. He inherited his father's official post within the shogunal fire-fighting organization (jōbikeshi), which protected Edo castle and the residences of the shogun's retainers. The majority of samurai retainers lived in chronic poverty and were forced to take side jobs to supplement their meager stipends. At age thirty-one, Hiroshige began to study under the ukiyo-emaster Utagawa Toyohiro, who gave him the artist's name by which he is remembered. He subsequently led a very successful career in designing series of color landscape prints, such as the famous Fifty-three Stations of the Tokaido, 1832, and was considered the foremost artist of topographical prints, best known for capturing the atmospheric effects of place and season. Only a few years after commodore Matthew Perry's mission to open Japan to the West in 1853–54, Hiroshige produced the most ambitious series of his career; prior to this work, landscape print series never attempted so many individual views. Issued between 1856 and 1858, One Hundred Famous Views of Edo was called Hiroshige's "grand farewell performance," since he died in 1858, during a cholera epidemic. The series, actually comprising 118 prints, remains not only the last great work of Japan's most celebrated artist of the landscape print but also a precious record of the appearance, and spirit, of Edo at the culmination of more than two centuries of uninterrupted peace and prosperity. Mark your calendars. If you are in the San Francisco bay area, this is a neat treat for textile fans.

When: 10am to 6pm, December 13 - 24 Where: The Language of Cloth 650-A Guerrero St. San Francisco, CA From SF Station: Pop-up shops come and go—one that has popped up consistently in the Mission over the years is the language of Cloth, on Guerrero near 18th Street, steps away from Tartine, and the Mission gourmet corridor. Each year a long narrow garage is transformed into a veritable silk road of textile treasures. Proprietor, Daniel Gundlach travels most of the year throughout Southeast Asia to find hand made cloth, scarves, shawls, sarongs, bags, wall hangings, clothing, ceremonial and ethnic textiles, and accessories for the home. When he is not searching the backroads of Southeast Asia, Daniel is busy in his small workshop in Yogyakarta, Central Java, collaborating with local batik makers to produce his own unique designs in batik on hand woven silk and other fabrics. This year’s the language of Cloth pop-up shop is themed sutera, the Indonesian word for silk. It is all about silk and features beautiful hand woven scarves, made from the silk collected from the wild indigenous silkworms of Java, colored by nature in shades of gold and chocolate. This year’s shop will expand into an adjacent space for the first time, to include a collection of mid-century modern kimonos, haoris, and obis. The surprisingly bold and colorful designs are not of the subdued quality usually associated with Japanese design. Passing through the length of the shop is like taking a mini textile tour of Southeast Asia where you can see hand woven silk scarves from award winning weavers from Laos, lustrous silk cloth from Issan Northern Thailand, hand drawn batik on silk from Java, and ethnic textiles from tribal areas of Burma. Daniel hand selects every piece with the eyes of an artist, sensitivity to the needs of the artisans, and with an awareness of the impact on the environment of their production. He is deeply committed to preserving the cultural integrity of textile artisans and indigenous textiles. He always stocks a wide selection of affordable and beautiful textiles under $20. http://www.thelanguageofcloth.com/ |

About UsPoetic Pillow is a platform for creating meaningful space. A room, a home, an office, a garden, any space that we inhabit can be made special by pillows. Decorative throws, pillow covers, and cushions, in all its possibilities can transform a space from ordinary to meaningful.

Archives

September 2023

Categories |

CUSTOMER SERVICE |

|

RSS Feed

RSS Feed